Different perspectives on sheltering in place:

Challenges in the housing-insecure community

PROJECT LEAD: Devika Patel

PROJECT CONTRIBUTORS: Devika Patel, Josh Feler, Lara Chehab, Adrienne Baer, Aashna Shah, Sneha Ayyagari, Raga Ayyagari, Sarah Salameh, Bhavna Hariharan, Dr. Keisuke Nakagawa, Dr. Theresa Cheng, Dr. David Rosenthal

AUTHOR: Devika Patel

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

Social distancing and adhering to public health recommendations are difficult, especially if you and/or your family are unhoused. To characterize the myriad of complex challenges facing the housing-insecure community, our team interviewed 15 stakeholders from the community, including unhoused individuals, front-line workers, and local government leaders in SF, Chicago, New Haven and others. Each city and community to which we spoke has responded to these challenges in unique ways. Through our ethnographic research, several insights have emerged that we would like to share.

INSIGHTS & RESEARCH

Challenges are local. Each municipality faces a distinct combination of logistical, political, and social obstacles to providing appropriate care; each has a different set of resources available to address them.

The unhoused population is seen as homogenous, when it consists of heterogeneous groups and individuals with varying needs and wants. Not all unhoused individuals face the same challenges, and their unique life circumstances warrant a tailored approach.

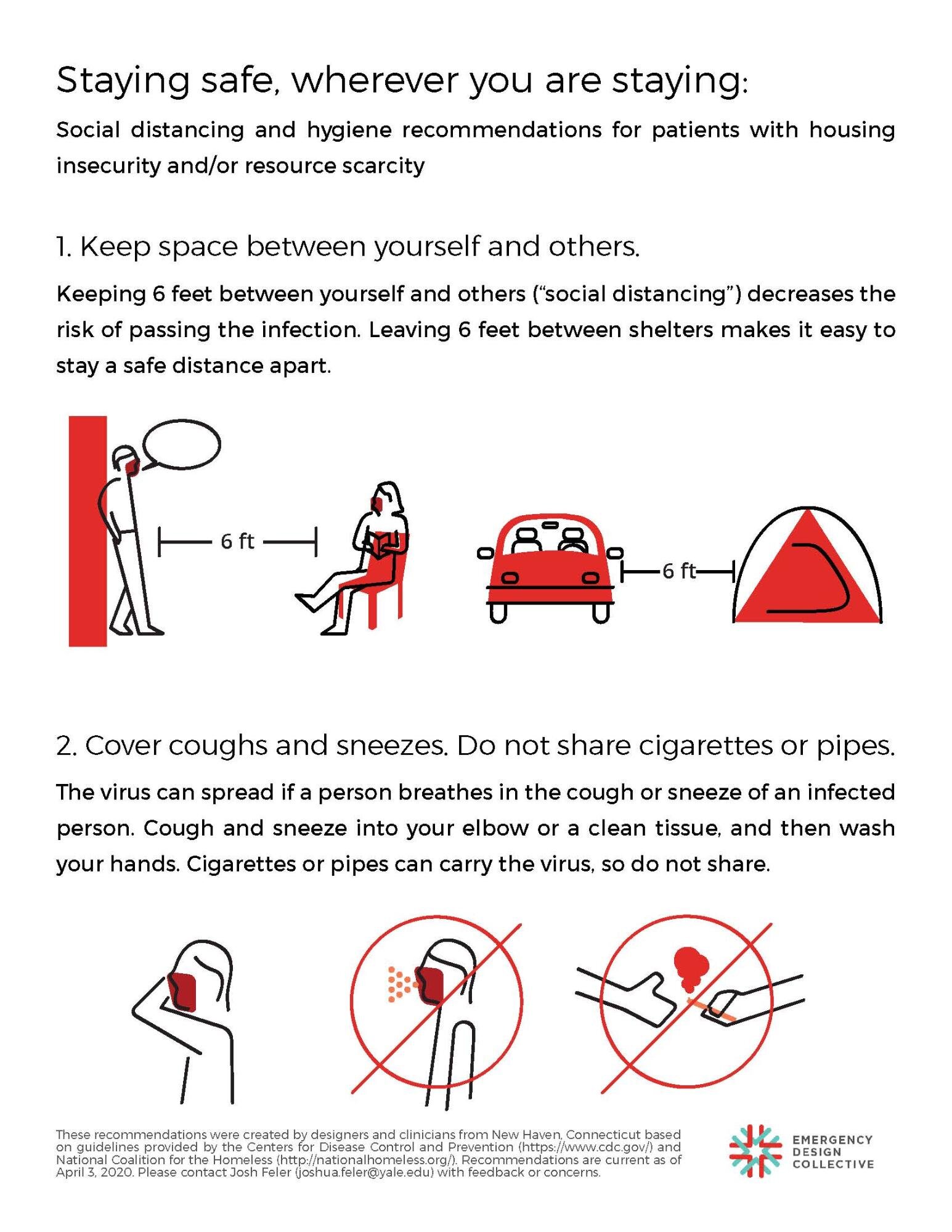

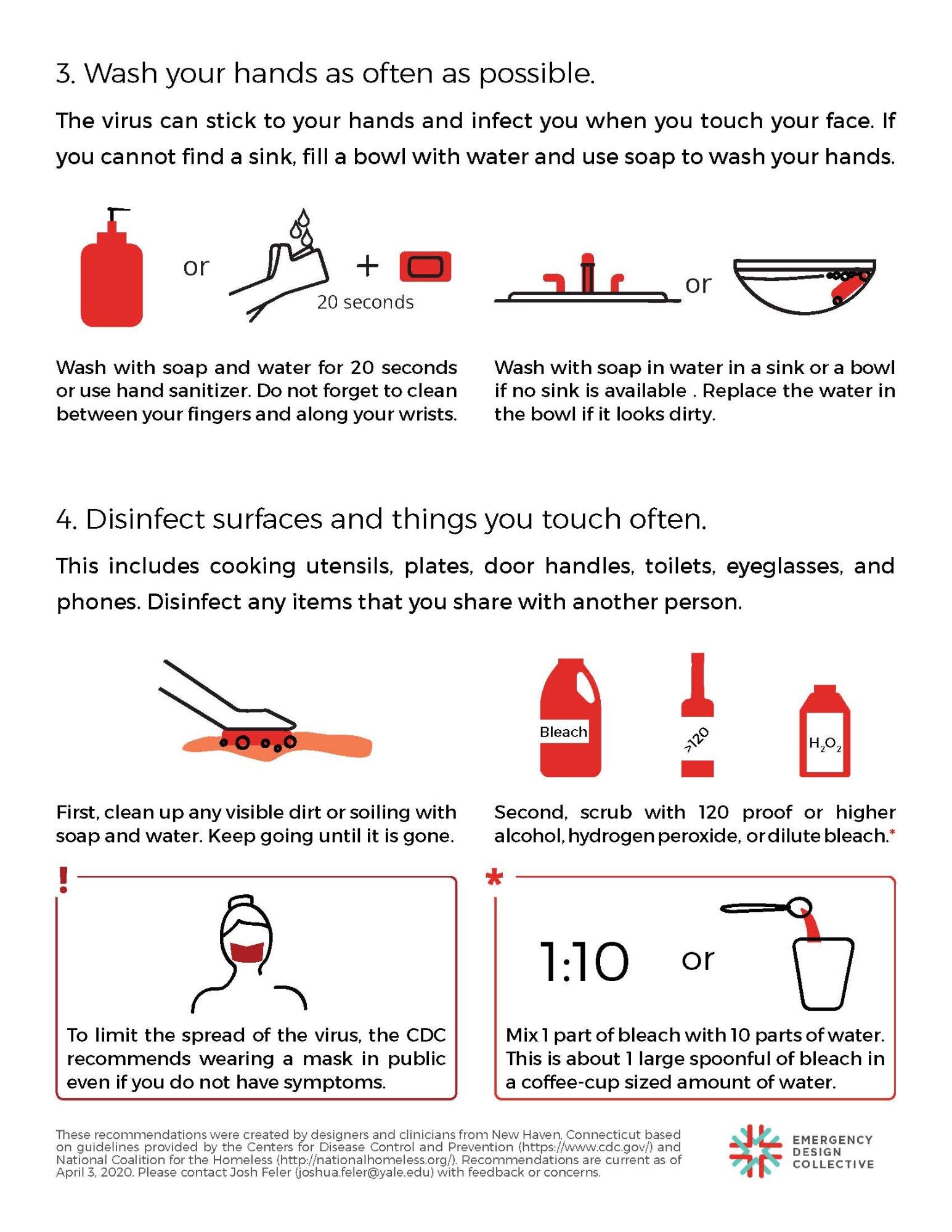

Recommendations for the general public may not map directly into the experience of housing insecurity. For instance, we see this in the case of social distancing: the ability to effectively social distance / practice hand-hygiene is variable among this population. Resource scarcity and access to hygiene facilities require adaptation of recommendations to accommodate these realities. For those living unhoused, access to water is a specific concern.

Supporting those with housing instability depends on in-person communication, but in-person outreach is risky. The urgent need for regular communication is further confounded by the fact that tracking and staying in touch with community members is a challenge, even under normal circumstances.

Knowledge sharing is invaluable at every level - from program building to front-line management to policy-makers - but is not always implemented. Frontline providers are looking for resources and have constructed informal communication channels via technologies like Slack to share information.

Changes to laws have not been communicated well to either the unhoused communities or the front-line workers. Laws impacting the location and length of time that an encampment can remain in place have shifted; encampments remain migratory.

Boredom is rampant. Social distancing has led to the cancellation of many activities and the closing of many facilities that were used by the housing insecure community.

Four walls may not equal safety. Shelters are not designed to enact social distancing between residents as they share resources like restrooms. They lack widespread guidelines for the management of outbreaks.

Four walls may not be a gift. Placing many cots in a large room might be efficient, but it affords no privacy. Placing folks in hotel rooms may also not be the right solution. Residents may feel criminalized in ‘quarantine.’

NEXT STEPS

Our team is working on brainstorming and prototyping communication materials focused on providing up to date information around a variety of COVID-19 related topics for both the unhoused community and the providers caring for them.

CALL TO ACTION

We need your help to test and give feedback on our materials, as well as help distribute and disseminate.